Why We’re Here

“Freedom For” Rather Than

“Freedom From”

Lou Tice didn’t just teach—he revolutionized how change happens. His insight? Stop running from problems and start chasing possibilities. With Lou’s brilliance as the wind at our backs, The Pacific Institute has turned this mindset into millions of transformed lives.

Often presented with , “Lou, you saved my life,” Lou would typically reply, “Actually, you saved your own life. I just gave you the tools to use.”

How did Lou impact your life? Leave a testimonial

Today

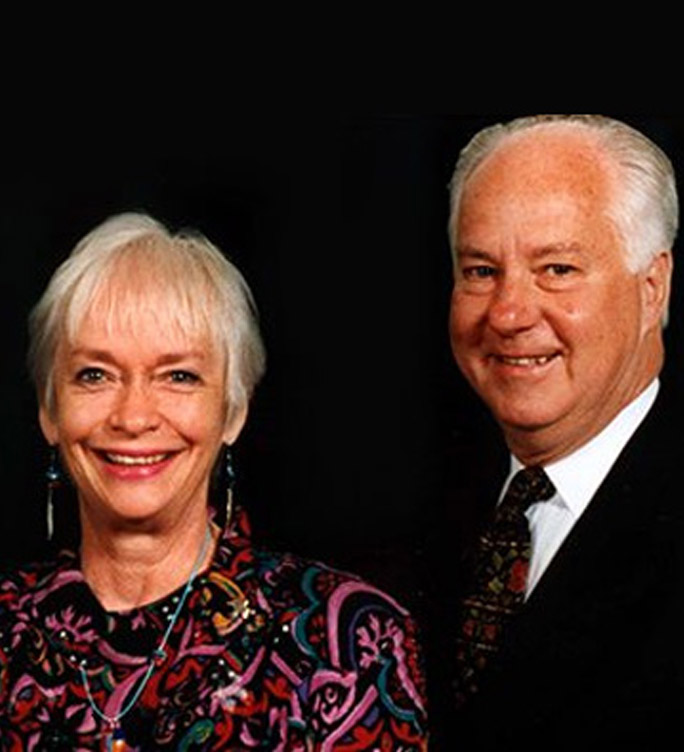

The Legacy Continues

Today, Lou and Diane’s vision thrives in 60+ countries across 6 continents in 20+ languages. Leaders of industry, teachers, generals, athletes, and everyday folks have become their students, and a new generation now carries forward Lou’s core mental technology, translating it for our new world of work.

Were you inspired by Lou Tice? Join us in advancing his mission and help your organization thrive from the inside out.

Video Collection

The Vault: Where Lou’s Words Still Change Lives

Step into Lou’s most powerful moments with this collection of the very best of our founder’s wisdom.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

“All meaningful and lasting change starts on the inside and works its way out.”

— Lou Tice